The empty stands at the ongoing AFCON games have become a popular topic among sports critics and enthusiasts. Mid-year 2025 (June – July), I watched nearly every WAFCON (Women’s AFCON) match, which also took place in Morocco, where the men’s AFCON is. The fan stands were way emptier than what AFCON is experiencing, with its highest attendance as low as 21,000.

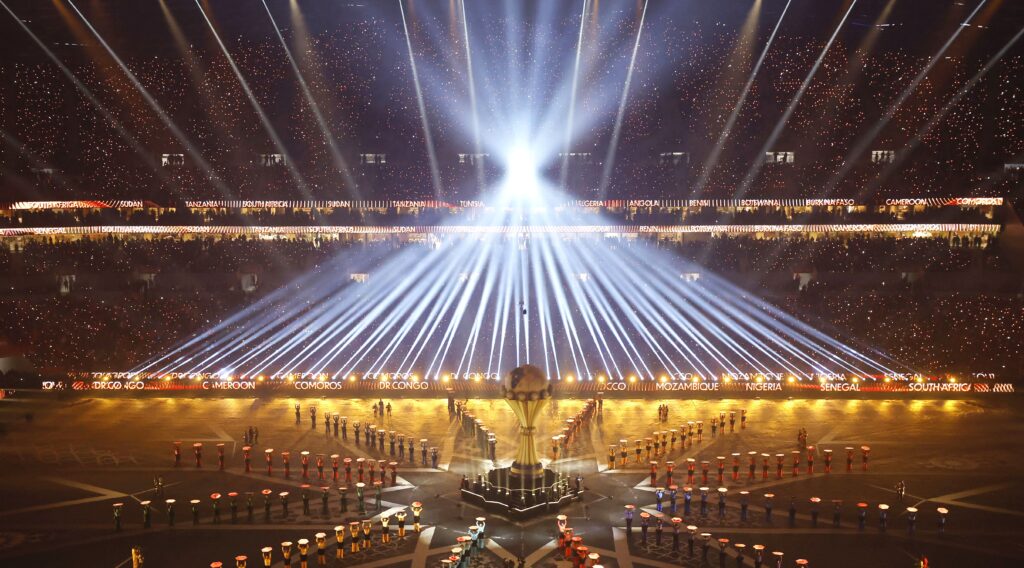

The AFCON games are still taking place, and presumably, as the games go into the knockout stage, it’s natural to assume that the crowds may gain some larger traction. So far, the record attendance was set by, the Morocco vs. Mali at 63,844 fans, and the lowest attendance has been 4,013 fans at the South Africa vs. Angola game. For the 2024 WAFCON games (which took place in 2025), the highest attendance was around 21,000 (figures not clearly declared) for the final between Nigeria and Morocco. The tournament generally had a low turnout throughout the games.

The record for the highest attendance at AFCON games is held by Senegal vs. Egypt 1986 and Algeria vs. Nigeria 1990, both hitting a high of 100,000 fans. For a continent with over 1.5 billion people, these numbers should be elevated beyond what they stand at.

Over Christmas, we met as Ugandans in our small diaspora community. As usual, politics is always one of the hot topics, and more so at a time like this when Uganda is holding elections. One of the arguments at hand was, “The establishment of modern facilities, like a world-class health facility in a remote district like Karamoja (one of the most remote underdeveloped regions in the country), would lead to development of the region.” While I was on the proponent side, one of the opponents to this had a number of questions at hand: “Why should someone move from Kampala, the capital city, to seek medical help in Northern Uganda? Why would a doctor accept to leave Kampala and work in this facility? Why should a local person in Karamoja go to this hospital if, at the moment, they can’t go to the small health centers?” He concluded, “You will establish a world-class facility, and it will only be a structure, but without any activity in it.”

As a sports management student, I actually understood his argument, but to keep the conversation afloat, I had to stubbornly keep opposing him. The questions he posed are the exact questions every sports salesperson (clubs, tournaments, and leagues as well) is faced with every day: “Beyond having a world-class sports arena, how do we get people to attend the games?” In fact, just like we argued that a ‘world-class facility’ would automatically be a force for development, we fell into the fallacy in sports that ‘a winning team will automatically cause the arena stands to fill up.’

Before all is said and done, economic empowerment is a top challenge across the African continent that needs to be addressed. This is definitely beyond AFCON, as it cannot control what African economies look like, but it must be addressed as being part of a sports experience, like the AFCON comes at a cost. Each year in February, the second or third Sunday leaves USA streets empty, and fans’ stands filled up at whatever field the NFL Super Bowl is taking place. Interestingly, the price to the Super Bowl is not laughable pocket change. Last year, the cheapest ticket was $5000, and this year, with the Bowl insight, the prices are already hitting highs of $6000 – $8000. To your amusement, the Super Bowl always sells out, and the fans’ stands are crowded. Let’s talk purchasing power (or disposable income, since this is what someone is most likely to use to purchase a sports/leisure-related ticket). Unfortunately, Africa is not a country, so there are many numbers to break down, but the average income earned across the continent is $2000 per annum (This figure is subject to change as it can be lower in low-income countries like Burundi or higher in countries like Libya and Mauritius). Considering the average income earned, how much disposable income does someone get to keep? Disposable income is the money one is left with after they have taken care of all their basic needs and utilities. Not much is considerably left comparing the average annual income to the cost of living in most African countries.

Unfortunately, with little disposable income left, a better question is posed: why should someone purchase a ticket or save to go to the AFCON games? In economics, every business, regardless of the sector, they are competing for the same dollar. In short, why should someone save to go to AFCON instead of buying a ticket to go to tour Europe, or spend the money at the local casino, or go to Zanzibar for vacation?

Last year, I wrote an article about sports not being a standalone event, but packaged as sports and entertainment (including leisure). I exemplified with college football, which can attract 10,000s of crowds each weekend. And interestingly, out of these crowds, nearly half (or even ¾) are at the game for reasons beyond football. In fact, I can re-echo some of the most aired views by people: “Honestly, I don’t even understand the game,” “After the first quarter, I don’t even know what is happening,” “I go for the drumline (the entertaining band at college football),” among other reasons. And for a better understanding, one of my professors said, “Even if it means getting that one guy to come to the game because he will get to stare at the butts of the cheerleaders, then go ahead, at least we know we shall have a fan in the stands.”

To sum this up, beyond the action on the field, given that this is a tournament, what more is there, such as in-game experiences, that will make a fan want to travel all the way from South Africa to Morocco? Is it the halftime fans’ engagement like field game challenges (to win grand prizes such as a car – that will get people off their televisions to the stadium, hopefully to win), or the t-shirt toss during a water break, or considering the love of music and dancing by Africans (do we have artists performing at every halftime)? Or do we have exclusive fan stands where an ordinary person can also access VIP treatment?

Lastly, intentional partnerships and sponsorships should be one of the key things AFCON looks at. One of the biggest partnerships this year is Orange Telecom. As stated earlier, one of the hurdles to having fans at these continental tournaments is the fact that Africa is a continent, not a country. For example, Orange was a popular brand in Uganda that phased out in the mid 2000s, yet it’s thriving in other countries like Morocco. Therefore, this limits the scope within which its partnership will be noticed or exploited. In that the effort it’s putting in those countries is nearly watered down in the countries that don’t have Orange. Think of an SMS sent out by Orange on a daily basis to its users about the tournament as a marketing effort, or each time someone uses their service, below the service acknowledgement or receipt, Orange reminds them about the tournament, either through a tagline or call to action. Beyond just Orange, the tournament is labeled TotalEnergies African Cup of Nations; in this case, Total operates in nearly every African country. This is an opportunity that the tournament can jump on to have marketing efforts across the continent get to even the local trader who only buys paraffin from Total or that child who buys sweets from its shops at the petrol (gas) stations. Push brochures, give offers tied to the tournament, hold marketing rallies (these are still very successful in most African countries where a truck has loud music playing, an MC, dancers, and free goodies like AFCON themed shirts), and tie some purchasing incentives to the tournament (such as fuel at Total and stand a chance to win tickets to all the playoff games. Even if Total got a winner from all African countries, that would at least add 54 more fans in the stands. In the long run, this offer would get even the tuk tuk driver in Tanzania to care about AFCON despite not winning).

Conclusion

Quite a long read, and yet I still feel like I left a lot untouched. I was recently pondering why AFCON is a top tournament on the continent, but it’s still struggling beyond just the issue addressed in this article. Particularly, I am puzzled when most Africans ask questions like, “Is AFCON a qualification tournament for the World Cup?” Or when an African diehard for the English Premier League states, “I don’t even know anything about AFCON apart from the fact that one or two of our players won’t be playing the next couple of EPL games.”

This leaves a question for you and me: “Is there a communication gap between fans, could-be fans, and the tournament itself?”