Part One

Not so long ago, a basketball personality in Uganda got married, and incidentally, he married an old girl (OG) of mine from high school. Definitely, in our old girls’ groups, despite failing to be productive, “tea” will never miss. Someone shared pictures of the happy couple, and this gave us an adrenaline rush of something to blabber about for as long as anyone had something to say. The biggest question in the group was, “Do basketball players in Uganda earn enough?” Everyone questioned the man’s financial ability to marry a woman of her stature. Often, I was put in the limelight, since most people know I am into sports, but I constantly jumped my way out of the question.

Recently, another old girl reached out, puzzled about advances from a one athlete who has, in fact, played on the national basketball team for over a decade. Her worry was, “Does he earn enough from sports?” I laughed and told her to go and come back and tell me.

It’s puzzling to learn that the poverty that reeks amongst Ugandan athletes has nearly become a concern to affect how significant others perceive them or their worth. And yet again, what’s more puzzling is a system that continues to perpetuate this poverty. It’s not only the men athletes that are under the scrutiny of society; the women face it worse. For every budget towards sports, women receive a slice of the pie. If a male basketball player is receiving Ugx 10,000 (less than $3), the other gender usually receives half of that. Rarely will they receive the same amount. And this plays out in the salary earned and awards given.

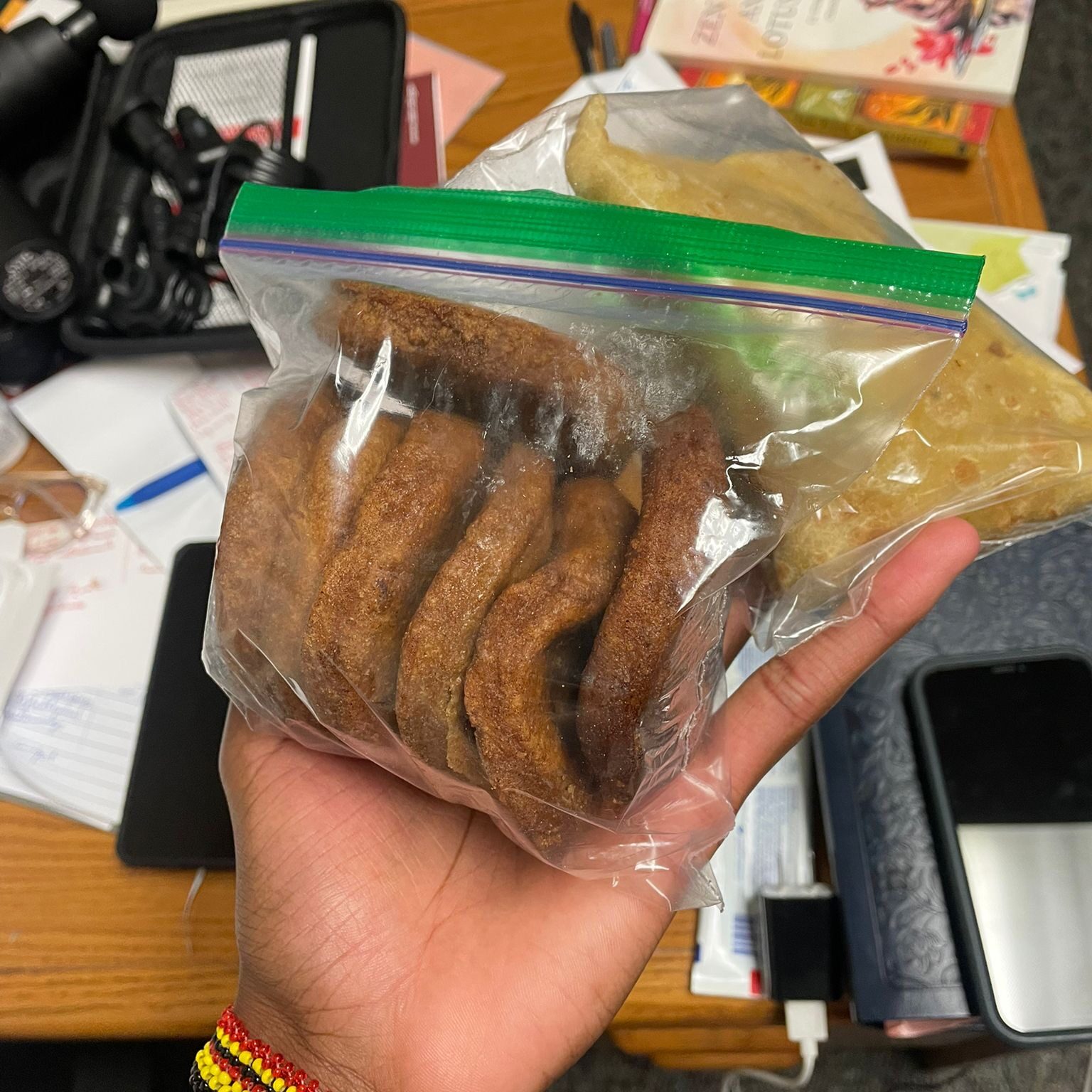

Most players in the Uganda National Basketball League (NBL) earn less than UGX 500,000 (approximately $145 per month), and this is for the top three teams in the women’s and men’s divisions. A handful have beaten this threshold. But even with this, the money comes with a lot of problems, especially delayed payments, which can last from one month to a year. I can’t count how many athletes have reached out asking for just UGX 20,000 (less than 6 dollars) to get a meal or afford a boda (ride) to practice.

Actually, what is stated above would be placed at 3 on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being the best. Most lower division players play to play (unless there is a better way this could be stated). The most they receive is a drink from a teammate who received his or her salary and felt like spoiling their teammates. The lower division probably wouldn’t make it to the scale. And yet these heroes show up for practice every day and suit up every game day to entertain fans who have paid an entrance fee that falls between UGX 5000 – 10,000.

Beyond the measly paychecks that arrive months late, there is the burden of medical bills, especially when the athlete gets injured. The injury often is an early dismal from sports, setting the athlete into a spiral of depression and anger. Loaded with questions which will never be answered, the athlete has to run up and down looking for donations, adding UGX 1000 to UGX 1000 (less than a dollar) to make UGX 10,000,000 (approximately USD 2800).

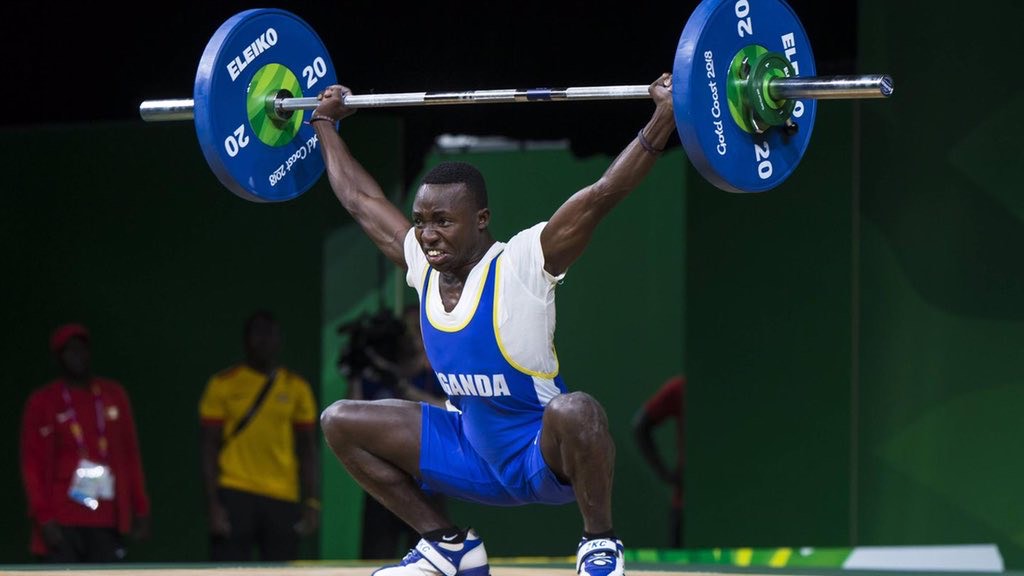

This is the reality for all sports disciplines in Uganda. Basketball is just a representation of other sports.

The NBL recently came to an end – congratulations to Namuwongo Blazers for bagging their first championship and to JKL for winning their ninth title. For the sake of privacy, I will refer to the athlete I chatted with post the championship games. I reached out to congratulate them on the win. They were definitely ecstatic about the victory. I jokingly asked them to share with me the money they were going to receive. They laughed and said, “We only get medals.” I asked about the grand prize, which the team receives, to which they replied, “It goes to management.” I was speechless. These players had given us a good series, and even if they had not given us a mind-blowing series, monetary appreciation would have gone a long way.

Part Two will be out next week. Thank you for reading.